J_Bus_Account_Financ_Perspect 2020, 2(3), 15; doi:10.35995/jbafp2030015

Article

Corporate Social Responsibility and Cost of Equity: Literature Review and Suggestions for Future Research

1

Universidad Carólica de Santiago de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador

2

Departament de Contabilidad, Universitat de Valencia, Valencia, Spain; ana.zorio@uv.es

*

Corresponding author: luis.garzon@cu.ucsg.edu.ec

How to Cite: Renato Garzón-Jiménez, Ana Zorio-Grima. Corporate Social Responsibility and Cost of Equity: Literature Review and Suggestions for Future Research. J. Bus. Account. Financ. Perspect. 2020, 2(3): 15; doi:10.35995/jbafp2030015.

Received: 22 October 2019 / Accepted: 20 April 2020 / Published: 30 April 2020

Abstract

:Listed companies have become increasingly aware not only of the importance of being socially responsible but also about reporting their initiatives in this field. Existing research has investigated many of the impacts of the sustainable profile of companies on a wide range of financial dimensions. The link between the cost of equity and sustainability is extremely timely as it can have great potential in reinforcing good practices regarding sustainable engagement amongst listed companies, which can also be regarded as trendsetters by other types of companies and institutions. This paper presents a thorough literature review of 22 articles focused on the link between sustainability and the cost of capital. The main contribution of this study is the broad scope of the literature review not only regarding the number of papers revised but also the provided details and their systematisation, such that future researchers in the field can easily identify the references regarding, for instance, different theoretical approaches. The methodologies that have been used to test the hypotheses as well as how the cost of equity is proxied by the different authors is presented together with the independent variables for measuring the sustainable profile of companies as well as the control variables. Our literature review also pays special attention to the different regional settings where research has examined the link between the cost of equity and sustainability and presents new ideas for studies in the field in order to open up future avenues for research.

Keywords:

cost of equity; CSR; sustainability; literature review1. Introduction

Unethical business practices are nowadays under the spotlight, attracting the attention not only of the justice system but also of the media, due to the increasing awareness of the need to protect Planet Earth. Therefore, firms make significant efforts not only to take actions to protect the environment, the quality of life of their workers, and local communities but also to communicate those initiatives to a wide range of stakeholders, including, of course, the shareholders, as many of these firms have trade shares in international equity markets. All these actions are under the umbrella of the so-called corporate social responsibility (CSR) of companies.

Indeed, CSR must be understood under the “triple bottom line” approach explained by Elkington (1998), which expands on traditional corporate reporting to consider social and environmental performance in addition to financial performance. In addition, the acronym “Environmental, Social and Governance” (ESG) is commonly used to refer to CSR activities because these are the three most important factors when measuring corporate sustainable behaviour.

Many studies have analysed the relationship between the CSR of the companies listed in capital markets using a wide range of financial dimensions (for instance, information asymmetry, earnings management, audit fees, cost of debt, debt ratios or equity ratios). Benlemlih (2017) presents a broad literature review in all these different areas, referring to only six recent articles until 2014 on the specific topic of cost of equity (CoE). Note that CSR disclosure is a potential mediator of the CSR–CoE relationship, but not an indispensable one, and there may be other types of impact in corporate finance. For instance, the positive link between CSR and corporate financial performance (CFP) is also evidenced when companies with higher CSR scores have greater CFP reflected on return over assets (Waddock and Graves, 1997). CSR disclosure increments resources to finance profitable projects, thereby reducing capital constraints (Cheng et al., 2014) and increasing the firm’s market value, especially in weak equity and debt markets with higher transaction costs (El Ghoul et al., 2017). Hence, and especially for listed companies, CoE is a very powerful indicator in financing and strategical decision making. It represents the return or percentage gain capital providers will obtain by investing on the firm’s shares, which can be measured according to different definitions or proxies. These expected returns are valuable for capital budgeting, portfolio allocation, performance assessment, active risk control, and even firm valuation.

Our study is timely and valuable as this is a growing area of research and the latest literature review only revised six articles on CSR and CoE covering up to 2014 (Benlemlih, 2017). Note that the European Union requires greater disclosure of nonfinancial and diversity information by large companies (Directive 2014/95/EU, 2014). European countries have transposed this directive such that companies are required to include some nonfinancial information in their annual report or separate reports from 2018 onwards. Therefore, the new requirements imply a new setting where future research will try to assess the impact of increased CSR engagement on financial aspects such as CoE. In addition, companies might be even more willing to make new disclosures on sustainability if new evidence is found for the benefits of CSR regarding CoE reduction. Therefore, the contribution of this literature review study relies on its extension (22 articles), covering a wide time span from its origin in research (2001) up to the latest publications in 2018, at a time when more requirements for sustainability disclosure are being introduced in the European Union, and when there is also an increasing trend to inform about nonfinancial information around the world. Hence, the topic of CSR and CoE becomes even more attractive for future researchers, managers, or society as a whole.

The definitions and methodologies used to measure CoE are diverse, and there is also a wide range of variables measuring the sustainability profile of a company. Henceforth, the main purpose of this article is to present a literature review of the relationship between CSR and CoE on an international scale, focusing on the theoretical frameworks referred to, the methodologies employed, the different approaches to measure the cost of equity together with the sustainability measures and control variables, and the regional settings examined, with the aim of providing a base for future research.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 explains the methodology employed to define the scope and sample of the studied articles. Section 3 describes different theoretical frameworks, the models implemented by authors to calculate the cost of equity, the independent variables required to measure the sustainable profile of firms, and control variables. Additionally, we analyse different regional contexts where the research between CoE and CSR has been examined through the years. The paper closes with the conclusions section, with new ideas for studies in this field in order to open future avenues for research within this specific topic—i.e., suggestions related to innovative studies on CSR and CoE.

2. Method

In order to select the sample of articles for our literature review, we searched for the keywords “sustainability”, “CSR”, “corporate social responsibility”, “cost of equity”, and “cost of capital” between 2008 to 2018 in both Google Scholar and Web of Science (WOS) from the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI). The time period was selected to cover the last decade in order to provide a spectrum wide enough to reflect a period when corporate social responsibility has been on the agenda worldwide, and especially in Europe, as it can bring benefits in terms of risk management, innovation capacity, cost savings, customer relationships, access to capital, and human resource management1. The search was refined by checking that the contents were really focused on the target relationship under analysis, and that the journal is covered by WOS. The article by Richardson and Welker (2001) was also finally included in the sample because of its impact and its pioneering approach. The final sample comprises 22 articles (see Table 1, which illustrates their impact through the citations in WOS).

The earliest articles on CoE are based on the capital asset pricing model of Sharpe (1964) and Lintner (1965) and the three-factor model by Fama and French (1993). These early studies were mostly undertaken in the US setting because of the importance of their capital markets and data availability, analysing financial and corporate variables other than sustainability, since companies did not really disclose CSR information in those days. Table 1 shows that the first article clearly referred to CoE and sustainability goes back to the turn of the millennium and focuses only on social disclosures as well as financial information (Richardson and Welker, 2001). Table 1 shows the articles revised in our study.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Theoretical Frameworks

Existing research on CSR and CoE is framed mostly within three theories, as follows.

According to the legitimacy theory, companies face different political and social pressures from various stakeholders. Hence, firms might feel pushed to adopt a “social” behaviour to legitimise themselves (De Villiers and Van Staden, 2006) or disclose CSR information by facilitating media coverage so that society can accept the company’s business practices (Li et al., 2017). These disclosures may be manipulated by companies to maintain a socially responsible image (De Villiers and Marques, 2016). Controversial (e.g., mining, tobacco, gambling, and sexual activities) or sensitive industries often create negative externalities (Hong and Kacperczyk, 2009; El Ghoul et al., 2011), so these firms are expected to disclose more detailed ESG information in order to legitimise themselves and reduce their CoE by compliance with social norms to establish business operations and good relations with stakeholders (De Villiers and Marques, 2016).

Out of the 22 articles under analysis of CSR and CoE, 4 articles (18%) refer to legitimacy theory (Li et al., 2017; Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez, 2017; Michaels and Gruning, 2017; Weber, 2018). In line with promoting a good image among stakeholders, CSR represents an important variable to improve firm’s legitimacy by receiving favourable news coverage (Li et al., 2017) and increasing its credibility with external assurance (Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez, 2017).

Agency theory is based on the “stewardship problem” between principals (shareholders) and agents (management), since the latter may act according to their “economic self-interest”, possibly expropriating the firm’s assets against the shareholders’ interest because of misuse of private information. Furthermore, shareholders must incur costs to monitor agent’s activities and bear risk (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Voluntary disclosure (such as CSR information, for instance) reduces information asymmetries by reducing transaction costs, increasing the demand of shares, and consequently decreasing CoE (Diamond and Verrecchia, 1991). Moreover, shareholder’s future risk estimations decrease and, finally, non-diversified risk also diminishes (Coles et al., 1995; Clarkson et al., 1996). The agency theory also provides a framework in the sense that management can be encouraged to pursue and disclose CSR activities in order to maximise salary bonus, secure job positions, and avoid future conflicts with stockholders (Healy and Palepu, 2001), reducing information asymmetry and the company’s financial uncertainty (Richardson and Welker, 2001; Verrecchia, 2001). In addition, voluntary external assurance of nonfinancial information (Sierra et al., 2014; Zorio et al., 2014) reduces agency conflict and their CoE (Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez, 2017). In spite of all the literature above, Breuer et al. (2018) cite agency theory in anticipation of a positive relationship between CSR and CoE as they argue that CSR can be a costly diversion of scarce resources.

Out of the 22 articles reviewed for this literature review, 6 articles (27%) refer to agency theory (Gupta, 2015; Feng et al., 2015; Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez, 2017; Suto and Takehara, 2017; El Ghoul et al., 2018; Breuer et al., 2018).

Finally, stakeholder theory posits that companies need to have good relationships with different agents—including employees, customers, suppliers, government institutions, and shareholders—as well as by practising and disclosing socially responsible activities. Regarding CSR nonfinancial disclosures, the firm’s objective is to inform stakeholders about the different socially responsible activities with the purpose of maintaining business operations, reducing financial risk and, consequently, the CoE (Li and Foo, 2015). Social arrangements determine the importance of different stakeholders. In fact, an empirical study related to CSR disclosures with companies operating in liberal market economies (United States and United Kingdom) and economies where the state leads a more important supervisory role in the economy (Spain, Portugal, France) concluded that firms with headquarters in state-led economies disclose more detailed stakeholder information (labour, environment, community) than firms in liberal market economies (Gallego-Alvarez and Quina-Custodio, 2017). As regards code of law countries, the state or government plays a major role in economic decisions and different social groups (e.g., unions, clients, providers of capital, suppliers) exert pressure to regulate political actions in favour of their interests (La Porta et al., 2008; Liang and Renneboog, 2017).

Finally, as regards our specific literature review on CSR and CoE, 10 out of the 22 articles (45%) are framed within the stakeholder theory (Richardson and Welker, 2001; El Ghoul et al., 2011; Reverte, 2012; Dhaliwal et al., 2014; Harjoto and Jo, 2015; Li and Foo, 2015; Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez, 2017; Michaels and Gruning, 2017; El Ghoul et al., 2018; Breuer et al., 2018).

Some of the analysed articles refer to a multifaceted theoretical approach (as Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez, 2017, who build on the three theories mentioned above). On the other hand, other articles in our specific review on CSR and CoE do not specifically refer to any particular theory. Note for instance Xu et al. (2014), who simply mention stakeholder theory as a keyword but do not refer to it in the text, or Li and Liu (2018), who refer to stakeholders and information asymmetry reduction yet do not properly build the conceptual theories behind this.

Other articles in our review (e.g., Dhaliwal et al., 2011; Reverte, 2012; Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez, 2017; Weber, 2018) also refer to voluntary disclosure theory (Botosan and Plumlee, 2005; Botosan, 2006), as sustainability engagement and CSR reports are used as a means to decrease information asymmetries and increase confidence in how social and environmental risks are managed (Li and Foo, 2015). From our point of view, this theory is very much in line with the postulates of the three theories above, being somehow a summary of the consequences of the other three explained theories.

3.2. Research Methodologies

Next, we explain the different methodological approaches of the 22 articles under study.

In most of the studies in our literature review, authors use regression analysis (Richardson and Welker, 2001; Sharfman and Fernando, 2008; Reverte, 2012; Feng et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2015; Li and Foo, 2015; Gupta, 2015; Eom and Nam, 2017; Michaels and Gruning, 2017; Weber, 2018; Li and Liu, 2018). Li et al. (2017) uses both ordinary least squares (OLS) and generalised least squares (GLS), while Weber (2018) uses a matched sample of GRI CSR with a propensity score as well as regression analysis.

Some studies address potential endogeneity and self-selection bias by carrying out two-stage regressions (2SLS) (as in Dhaliwal et al., 2011, 2014; Xu et al., 2014; Harjoto and Jo, 2015; Ng and Rezaee, 2015; Suto and Takehara, 2017; Breuer et al., 2018; Li and Liu, 2018) or the generalised methods of moments (GMM), following the technique developed by Blundell and Bond (1998), as in El Ghoul et al. (2011); Gupta (2015) or by Arellano and Bond (1991) in Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez (2017). El Ghoul et al. (2018) uses both two-stage least squares (2SLSs) estimation and a dynamic system with GMM.

3.3. Dependent, Independent, and Control Variables

In the 22 empirical studies of our sample, the dependent variable is the implied CoE, also called cost of capital in some studies. It can be defined as the percentage rate of return to obtain the market value of an asset by discounting future cash flows dividends (El Ghoul et al., 2011); or, in other words, the internal rate of return that investors expect to gain by maintaining their capital investment on the firm (Reverte, 2012; Suto and Takehara, 2017).

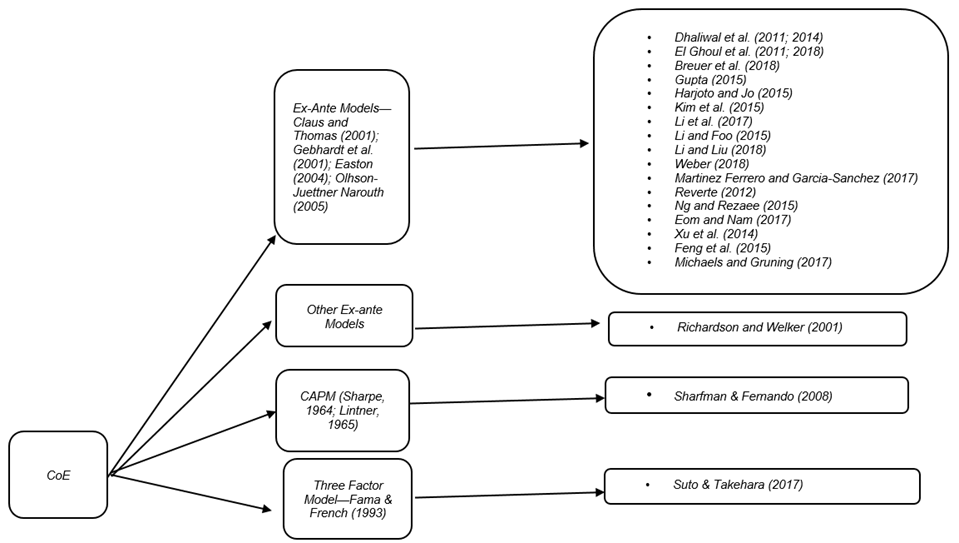

The models used to obtain the different proxies for CoE are shown in Figure 1.

In the majority of the 22 analysed articles, ex-ante models are used to calculate CoE considering forecasted earnings based on an analyst’s consensus and current prices. Reverte (2012) argues that the CoE obtained with ex-ante models is a better proxy than ex-post realised stock returns (by definition, a backward-looking measure). CoE is more reliant on cross-sectional variation amongst the companies, and it does not need long-time series to be robust and is not dependant on a specific asset pricing model. Gupta (2015) also supports the use of ex-ante models because they can account for unexpected news on cash flow or a firm’s fundamentals, which obviously cannot be not depicted in ex-post measures, and provides many examples of the growing volume of literature using this approach. Hence, the ex-ante models to calculate CoE in the articles in the sample follow mostly Claus and Thomas (2001), Gebhardt et al. (2001), Easton (2004), and Ohlson and Juettner-Narouth (2005). Note that Claus and Thomas (2001) assume the market price expressed as projected residual and book value earnings for a time horizon of 5 years and constant dividend payouts. Gebhardt et al. (2001) consider stock prices as return over equity projections with a time horizon from 2 to 12 years. The price earnings growth (PEG) model considers a time horizon of 2 years, projected earnings per share for year 2, year 1, current market price, and zero dividend payments (Easton, 2004). The previous model is recommended for CoE estimations by Botosan and Plumlee (2005) and Botosan et al. (2011), and implemented by Reverte (2012), Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez (2017), and Michaels and Gruning (2017). Out of the 22 studies on CSR and CoE, 19 (86%) implement this type of ex-ante model.

Gordon’s constant growth model is generalised by Ohlson and Juettner-Nauroth (2005), which defines the cost of equity using stock market price, one-year projected earnings, and perpetual growth rate. Ng and Rezaee (2015) proxy CoE with a variation of the price multiple—the industry-adjusted earnings–price ratio—as well as with the finite horizon expected return model (Gordon and Gordon, 1997).

In some studies (e.g., Dhaliwal et al., 2014; Li and Foo, 2015; Gupta, 2015; Breuer et al., 2018), CoE is calculated as an average of the three proxies developed by Gebhardt et al. (2001), Claus and Thomas (2001), and Easton (2004) and/or their further refinements, or even use the average plus some of the proxies, as in Xu et al. (2014). Some authors deduce risk free government note yields from the average result (Eom and Nam, 2017).

Ex-post models are also used to examine the relationship of CSR and CoE. For instance, the capital asset price model (CAPM) states that the expected market return is measured by implementing a single-variable stochastic model (Sharpe, 1964; Lintner, 1965). The model takes into account the risk-free data composed of treasury note debt yields; beta, which encloses the systematic relationship between the market and the firm’s individual risk; and, finally, the risk-free premium obtained by the difference between market return and the risk-Free rate. The CAPM approach is implemented to obtain CoE and analyse its relationship with environmental risk management disclosures in Sharfman and Fernando (2008).

Finally, other studies apply the three-factor model to obtain (or even explain) CoE. This model proposed by Fama and French (1993) considers additional variables, i.e., beta, the market-to-book ratio, and size (as in Suto and Takehara, 2017, following Fama and French, 1997). Note that some of the analysed articles used ex-ante models to estimate CoE and the variables in the three factor-model as control variables, as we explain in the next subsection (Dhaliwal et al., 2011; El Ghoul et al., 2011; Reverte, 2012; Li and Foo, 2015; Feng et al., 2015).

Some authors in our sample not only explore the relationship of CSR with CoE, but also with the cost of debt (e.g., Suto and Takehara, 2017), information asymmetry (Michaels and Gruning, 2017), corporate value through Tobin’s Q (Eom and Nam, 2017), or the firm risk and its investor base (Breuer et al., 2018).

The relationship between CoE and sustainability has been examined through many different lenses using a wide range of independent variables to contrast different hypotheses, controlling for different aspects somehow determined by the sample and, of course, including some kind of measure for CSR reporting or for the sustainable behaviour of the company.

Therefore, regarding independent variables, different authors provide several proxies. For instance, El Ghoul et al. (2011) uses a community score (based on volunteer programs, charity donations, relation with indigenous people, and taxes, among others), as well as an employee score and environmental score based on many other items. Reverte (2012) uses a CSR score quintile rank. Xu et al. (2014) use a CSR score, also taking into consideration partial scores as CSR investors (stockholder’s participation on firm’s decision making), CSR employees (health, salary, wages, social benefits, equal recruitment, etc.), CSR customers (R&D activities, consumer satisfaction, etc.), CSR suppliers (fair trade, protection of suppliers’ know-how), CSR community involvement (taxes, no child labour, anti-corruption policy, charities, etc.), and CSR environment (good environmental policies and management of pollutants, waste). Harjoto and Jo (2015) create a CSR index based on the disclosure items required by norms yet not by laws. Gupta (2015) further subdivides its main variable, environmental sustainability index (ESI), into three components, namely emission reduction, product innovation, and resource reduction. Michaels and Gruning (2017) develop a disclosure index based on an artificial intelligence model run on the actual CSR reports. Ng and Rezaee (2015) use an economic sustainability measure with three components—growth opportunities, operational efficiency, and research effort. El Ghoul et al. (2011), Dhaliwal et al. (2011), and Weber (2018) also consider if the company is a strong CSR performer or not. El Ghoul et al. (2018) use the ratio of environmental costs to total assets as a proxy for corporate environmental responsibility.

Reverte (2012) takes CSR into account through the ratings provided by the Observatory on Corporate Social Responsibility reports. Suto and Takehara (2017) use data on corporate social performance from an annual CSR questionnaire survey sent to all listed firms in Japanese capital markets. Richardson and Welker (2001) use social performance measures from Canadian society, that sponsored assessments of the annual reports.

Inclusion in a capital market index to indicate socially responsible investment has also been used as a proxy for sustainability (Eom and Nam, 2017).

Carbon information disclosure is obtained from CSR reports (Li et al., 2017, to calculate disclosure index) or from the National GHG Emission Information System of the Ministry of the Environment (Kim et al., 2015 to calculate carbon intensity as total GHG emission/sales).

Table 2 shows the CSR dimensions or measures studied by the revised articles, as well as the implemented methodology (e.g., OLS, GLS, and robustness tests).

Different control variables have been used by extant research (Table 3).

3.4. Sample Characteristics, Regional Settings, and Main Research Findings

In this section, we analyse the samples used by prior research, paying special attention to their size, covered period, and regional setting. Given the nature of the dependent variable (CoE), this type of study is obviously restricted to listed companies. Studies vary from having a very small sample size (114 observations in Reverte, 2012, in just one country, Spain) to having large samples in a multi-country setting (74,077 observations from 31 countries as in Dhaliwal et al., 2014, for instance).

The first study covered just three years (Richardson and Welker, 2001), whereas the latest data in the samples used correspond to 2002–2015 in Breuer et al. (2018). The more recent studies show many robustness checks, bearing in mind many different categories for some variables (for instance, the years in order to control for the effect of the economic crisis as in El Ghoul et al., 2018).

All of the studies confirm the negative relationship expected between CSR and CoE, except for Richardson and Welker (2001), and, in addition, Suto and Takehara (2017) and Eom and Nam (2017) do not find significant results.

The first study on CoE and sustainability covered 124 firms from Canada, with data from 1990–1992 (Richardson and Welker, 2001). Evidence was found of a significant positive relation between social disclosures and the cost of equity capita, even though companies had better financial performance.

However, most of the existing research demonstrates a negative relationship between CSR and CoE. In addition, the majority of studies are based on US samples because of the availability analyst forecast data. Sharfman and Fernando (2008) use a sample with 267 US firms, concluding that benefits from improved environmental risk management lead to a reduction in CoE. Dhaliwal et al. (2011) analyse 1190 CSR reports from 294 US firms, finding that companies with a high CoE in the previous year tend to initiate CSR disclosure in the current year, and that initiating firms with high CSR performance enjoy a subsequent reduction in CoE, attracting institutional investors and analyst coverage. El Ghoul et al. (2011) with a sample of 12,915 firm observations conclude that firms with better CSR scores have lower CoE, whereas belonging to “sin” industries (namely, nuclear power, and tobacco) increases CoE. Harjoto and Jo (2015) analyse 2034 US firms, demonstrating that, amongst other consequences, CSR intensity (more specifically, legal CSR) reduces CoE. Finally, Weber (2018) uses 878 CSR reports prepared under the G3 or G3.1 Guidelines from 2005 to 2013, finding that GRI disclosure level has not had an impact on CoE per se, yet a negative association for poor CSR performers reporting at high GRI level and CoE is observed, if the report is assured.

In Asia, and more particularly in China, Korea, and Japan, studies on this relationship have also been undertaken.

In China, Xu et al. (2014), using a sample of listed firms in Shanghai Stock Exchange, show that firms with higher CSR scores have significantly lower CoE, an effect which is more pronounced in times of economic recession. In addition, even though state-owned companies have better CSR and lower CoE than the others, the effect of CSR in reducing CoE is weaker in state-owned companies. Li and Foo (2015) use 1015 CSR report quality scores, finding evidence that CSR report quality is strongly and negatively related with CoE, with a much higher impact in lowering CoE for privately owned corporations, even though the distinction between mandatory versus voluntary CSR disclosures does not have a significant impact on CoE. Li et al. (2017) focus on 161 listed companies operating in heavily polluting industries, showing that media reporting improves carbon information disclosure (both financial and nonfinancial disclosures), which is negatively associated with CoE. Finally, also in China, Li and Liu (2018) analyse 1708 observations from 2008 to 2014, finding that the quality of the CSR disclosure is negatively related to CoE, especially amongst environmentally sensitive industries, state-owned enterprises, and those that are larger in size.

In the Korean setting, the sample of Kim et al. (2015) includes 379 firms from the period 2007 to 2011, concluding that carbon intensity is positively related to CoE, no matter whether the companies voluntarily published sustainability reports or not, with this effect being lower for firms belonging to industrial sectors with large carbon emissions. Eom and Nam (2017) use 86 companies listed in Korea, from 2009 to 2013. Their results cannot provide evidence of any significant relation between the incorporation of the SRI index and CoE or corporate value. Moreover, depending on the phase of introduction of the SRI index, the results revealed a negative or positive correlation with CoE, probably because of mixed optimistic and pessimistic expectations from investors about CSR activities, or because this index may not correctly reflect CSR performance.

Suto and Takehara (2017), using 3461 observations of Japanese firms, did not provide evidence of a significant relationship between corporate social performance and CoE, yet institutional ownership has a strongly negative influence on CoE.

In Spain, Reverte (2012), using only 114 firm-year observations from 26 firms covering from 2003 to 2008, finds a significant negative relationship between CSR disclosure ratings and CoE, which is even more pronounced for those firms operating in sensitive industries.

In Germany, Michaels and Gruning (2017) analyse the relation between CoE and CSR disclosures of 264 sensitive firms in 2013/2014. The disclosure variable was obtained through combining a series of coding schemes to score CSR disclosures. Results demonstrate that CSR-sensitive firms have greater equity costs but implementing voluntary disclosure decreases CoE.

In an international setting, several studies find evidence of the negative relationship between CSR and CoE. Using data from different countries obviously allows authors to explore the impact on national characteristics, such as stakeholder protection and governance or cultural variables.

Dhaliwal et al. (2014) using a sample with 5135 standalone CSR reports from 1093 companies find a negative link between CSR disclosures and CoE which is more pronounced in stakeholder-oriented countries. They also provide evidence that financial and ESG disclosures behave like substitutes in reducing CoE. The sample of Feng et al. (2015) includes 10,803 firm-year observations from 25 countries. They find evidence that, in general, firms with better CSR scores have a significantly reduced CoE in North America and Europe, yet these results do not hold in Asian countries (which is somehow contrary to the evidence obtained for China or Korea by Li and Foo (2015), Li et al. (2017), Li and Liu (2018), and Kim et al. (2015)) as explained above.

Ng and Rezaee (2015) use a sample with over 3000 firms (countries not explicit), from 1990 to 2013, finding a negative association between CoE and growth and research (environmental and governance) sustainability performance, with social performance being only marginally related to CoE. In general, the relationship is strengthened when ESG performance is strong.

Gupta (2015) uses 23,301 firm-year observations from 2002 to 2012. The obtained findings suggest that better environmental practices (mostly reduction of emissions and waste) lead to lower CoE, with this effect being more pronounced in countries where country-level governance is weak.

Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez (2017) use a sample of 1410 companies from 17 countries between 2007 and 2014, and find evidence of lower CoE for companies that publish and assure their social and environmental reports, especially if the assurance is provided by a Big 4 firm. Breuer et al. (2018), with a sample of 19,183 firm-year observations from between 2002 and 2015, find that if investor protection is high (low), CoE decreases (increases) if the company invests in sustainability. El Ghoul et al. (2018) analysed manufacturing firms in 30 countries from 2002 to 2011 and find that CoE is lower if companies have higher environmental responsibility.

In most of the studies in an international setting, we noted that the samples tend to be dominated by Anglo-Saxon countries because of data availability (for example, see Breuer et al. 2018 and El Ghoul et al., 2018).

4. Conclusions

This study presents a thorough literature review on the effects of CSR on CoE. We analysed the different theoretical frameworks, methodological approaches, variables under study, regional settings, and most important conclusions that can be drawn from all the analysed articles.

The study’s most important contribution to the literature is the updated and detailed revision of 22 papers studying the link between CSR and CoE. Note that the latest review of this kind (Benlemlih, 2017) has included only 6 papers and only up to 2014. We provide a precise understanding of what has been already investigated and the findings of prior researchers regarding the reduction in CoE due to sustainable behaviour. In addition, our review identifies certain gaps in the extant literature, detects inconsistent findings—e.g., Richardson and Welker (2001) find a positive link between CoE and CSR, contrary to expectations and Suto and Takehara (2017) and Eom and Nam (2017), which have inconclusive evidence. We also provide examples of possible data sources and control variables and provide directions for exploring new avenues of research in future studies.

This literature review shows that there are different methodologies to calculate CoE and that there are many possibilities to proxy for the sustainable behaviour of the companies, as well as many interesting control variables depending on the research setting. This paper is unique and valuable because of the high number of covered articles and its timeliness (with articles published up to 2018). Future researchers working in this field will hopefully find this review most useful when defining their own research variables in the design of their own empirical study and discussion of their own findings by providing comparisons with prior studies.

Our findings reveal that certain areas of the world have been overlooked by researchers in this field (for instance, the developing economies in Latin America or Africa). Therefore, future avenues of research might make valuable contributions to literature if they focus on these regions where sustainability should also be a priority, since the extractive industry is so important there and pollution needs to be mitigated to combat climate change. Along these lines, we think that it is most relevant that future researchers pay attention to carbon reporting and its effects on CoE (as Kim et al. (2015) and Li et al. (2017)) because of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of climate action. In addition, the trend to submit the CSR reports to external assurance in order to increase the credibility should also be contrasted so as to demonstrate that it can also reduce CoE (as initially explored by Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez (2017) and Weber (2018)). In addition, alternative methodologies can be used by researchers as shown in some of the analysed papers.

As limitations of our research, we acknowledge that focusing on the specific relationship between CoE and CSR implies that our study excluded many other papers that studied the links of CSR and other variables with CFP. On the other hand, keeping the sample focused on CSR and CoE allows for further extraction of details regarding the links between CSR and CFP than in the case of a much larger sample.

This type of research has practical implications for managers. The obtained evidence can motivate them to invest in sustainability initiatives in order to benefit from a lower cost of capital. The opposite may also hold, in the sense that if stockholders are concerned about social as well as environmental issues such as the depletion of natural resources, pollution, and global warming, the environmentally irresponsible companies will be penalised through a higher cost of capital.

References

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies 1991, 58(2), 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlemlih, M. Corporate social responsibility and firm financing decisions: A literature review. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 2017, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 1998, 87, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, C. A. Disclosure and the cost of capital: what do we know? Accounting and Business Research 2006, 36, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, C.; Plumlee, M. A. Assessing alternative proxies for the expected risk premium. Accounting Review 2005, 80(1), 21–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, C.; Plumlee, M. A.; Wen, H. The relation between expected returns, realized returns, and firm risk characteristics. Contemporary Accounting Research 2011, 28(4), 1085–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, W.; Muller, T.; Rosenbach, D.; Salzmann, A. Corporate Social Responsibility, investor protection, and cost of equity: A cross-country comparison. Journal of Banking and Finance 2018, 96, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate Social Responsibility and Access to Finance. Strategic Management Journal 2014, 35(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.; Guedes, J.; Thompson, R. On the diversification, observability, and measurement of estimation risk. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 1996, 31(1), 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus, J.; Thomas, J. Equity premia as low as three percent? Evidence from analysts’ earnings forecasts for domestic and international stock markets. Journal of Finance 2001, 56, 1629–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J. L.; Loewenstein, U.; Suay, J. On equilibrium pricing under parameter uncertainty. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 1995, 30(3), 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, C.; Marques, A. Corporate social responsibility, country-level predispositions, and the consequences of choosing a level of disclosure. Accounting and Business Research 2016, 46(2), 167–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, C.; Van Staden, C. Can less environmental disclosure have a legitimizing effect? Evidence from Africa. Accounting, Organizations and Society 2006, 31(8), 763–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.; Li, O.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y. Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. The Accounting Review 2011, 86(1), 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.; Li, O.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The roles of stakeholder orientation and financial transparency. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 2014, 33(2014), 328–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D.; Verrecchia, R. Disclosure, liquidity and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance 1991, 46(4), 1325–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups Text with EEA relevance. Official Journal of the European Union 330, 1–9. Retrieved from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014L0095.

- Easton, P. PE Ratios, and Estimating the Implied Expected Rate of Return on Equity Capital. The Accounting Review 2004, 79(1), 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O.; Kim, K.; Park, K. Corporate Environmental Responsibility and the Cost of Capital: International Evidence. Journal of Business Ethics 2018, 149(2), 335–361. [Google Scholar]

- El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O.; Kim, K. Country level institutions, firm value, and the role of corporate social responsibility initiatives. Journal of International Business Studies 2017, 48(3), 360–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O.; Kwok, C.; Mishra, D. Does Corporate Social Responsibility affect the cost of capital? Journal of Banking & Finance 2011, 35(9), 2388–2406. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with forks: The Triple bottom line of the 21st Century Business; New Society of Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, K.; Nam, G. Effect of Entry into Socially Responsible Investment Index of Cost of Equity and Firm Value. Sustainability 2017, 9(5), 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F.; French, K. R. Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics 1993, 33(1), 3–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F.; French, K. R. Industry cost of equity. Journal of Financial Economics 1997, 43(2), 153–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Wang, M.; Huang, H. Equity Financing and Social Responsibility: Further International Evidence. The International Journal of Accounting 2015, 50(3), 247–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Alvarez, I.; Quina-Custodio, I. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting and Varieties of Capitalism: An international Analysis of State-Led and Liberal Market Economies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2017, 24(6), 478–495. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt, W.; Lee, C.; Swaminathan, B. Toward an implied cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research 2001, 39(1), 135–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J. R.; Gordon, M. J. The finite time horizon expected return model. Financial Analyst Journal 1997, 53, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K. Environmental Sustainability and Implied Cost of Equity: International Evidence. Journal of Business Ethics 2015, 147(2), 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoto, M. A.; Jo, H. Legal vs. Normative CSR: Differential impact on Analyst Dispersion, Stock Return Volatility, Cost of Capital, and Firm Value. Journal of Business Ethics 2015, 128(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P. M.; Palepu, K. G. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Kacperczyk, M. The price of sin: the effects of social norms on markets. Journal of Financial Economics 2009, 93(1), 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.; Meckling, H. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Cost and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Management 1976, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; An, H.; Kim, J. The effect of carbon risk on the cost of equity capital. Journal of Cleaner Production 2015, 93, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Salines, F.; Shleifer, A. The Economic consequence of legal origins. Journal of Economic Literature 2008, 46, 285–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, Q.; Tang, D.; Xiong, J. Media Reporting, carbon information disclosure, and the cost of equity financing: Evidence from China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2017, 24(10), 9447–9459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, C. Quality of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Cost of Equity Capital: Lessons from China. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 2018, 54(11), 2472–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Foo, C. A sociological theory of corporate finance: Societal responsibility and cost of equity in China. Chinese Management Studies 2015, 9(3), 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Renneboog, L. On the Foundations of Corporate Social Responsibility. The Journal of Finance 2017, 72(2), 853–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lintner, J. The Valuation of risk assets and the selection of risky investments in stock portfolios and capital budgets. Review of Economics and Statistics 1965, 47(1), 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ferrero, J; García-Sánchez, I. M. Sustainability assurance and cost of capital: Does assurance impact on credibility of corporate social responsibility information? Business Ethics: A European Review 2017, 26(3), 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, A.; Gruning, M. Relationship of corporate social responsibility disclosure on information asymmetry and the cost of capital. Journal of Management Control 2017, 28, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.; Rezaee, Z. Business Sustainability performance and cost of equity capital. Journal of Corporate Finance 2015, 34, 128–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlson, J. A.; Juettner-Nauroth, B. E. Expected EPS and EPS growth as determinants of value. Review of Accounting Studies 2005, 10(2–3), 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverte, C. The impact of better Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure on the Cost of Equity. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2012, 19, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A. J.; Welker, M. Social disclosure, financial disclosure and the cost of equity capital. Accounting 2001, 26(7), 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfman, M. P.; Fernando, C. S. Environmental risk management and the cost of capital. Strategic Management Journal 2008, 29, 569–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, W. Capital Asset Prices: A theory of Market Equilibrium under conditions of risk. Journal of Finance 1964, 19(3), 425–442. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, L.; Garcia, M.; Zorio, A. Credibility in Latin America of corporate social responsibility reports. Revista de Administracao de Empresas 2014, 54(1), 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suto, M.; Takehara, H. CSR and cost of capital: evidence from Japan. Social Responsibility Journal 2017, 13(4), 798–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrecchia, R. E. Essays on disclosures. Journal of Accounting and Economics 2001, 32(1/3), 97–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, A. W.; Graves, S. B. The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal 1997, 18(4), 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. Corporate social responsibility disclosure level, external assurance and cost of equity capital. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 2018, 16(4), 694–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, D.; Huang, J. Corporate social responsibility, the cost of equity and ownership structure: An analysis of Chinese Listed Firms. Australian Journal of Management 2014, 40(2), 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorio, A.; García-Benau, M. A.; Sierra, L. Sustainability development and the quality of assurance reports: Empirical evidence. Business strategy and the environment 2014, 22(7), 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | See the European Competitiveness Report 2008 (COM(2008)774), as well as the accompanying Working Paper SEC (2008) 2853. |

Figure 1.

Cost of equity models used in the articles under study.

Table 1.

Articles studied and number of citations.

| Author | Citations |

|---|---|

| Richardson and Welker (2001) | 227 |

| Sharfman and Fernando (2008) | 285 |

| Dhaliwal et al. (2011) | 680 |

| El Ghoul et al. (2011) | 475 |

| Reverte (2012) | 69 |

| Xu et al. (2014) | 31 |

| Dhaliwal et al. (2014) | 118 |

| Feng et al. (2015) | 9 |

| Harjoto et al. (2015) | 48 |

| Ng and Rezaee (2015) | 30 |

| Kim et al. (2015) | 20 |

| Li and Foo (2015) | 11 |

| Gupta (2015) | 8 |

| Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez (2017) | 10 |

| Suto and Takehara (2017) | 3 |

| Li et al. (2017) | 6 |

| Eom and Nam (2017) | 5 |

| Michaels and Gruning (2017) | 8 |

| Weber (2018) | 1 |

| Breuer et al. (2018) | 4 |

| El Ghoul et al. (2018) | 18 |

| Li and Liu (2018) | 2 |

Note: Information obtained from WOS on 25 February 2020.

Table 2.

Corporate social responsibility and the cost of capital—equity literature: years, sample, regions, methodology, and variables studied.

Table 2.

Corporate social responsibility and the cost of capital—equity literature: years, sample, regions, methodology, and variables studied.

| Author(s) | Years Covered | Sample | Countries | Methodology | Independent Variables Studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richardson and Welker (2001) | 1990–1992 | 324 firm-year observations | Canada | OLS | Financial and social disclosures |

| Sharfman and Fernando (2008) | 2001 | 267 firm-year observations | USA | Multiple regression model | Environmental risk management |

| Dhaliwal et al. (2011) | 1993–2001 | 1190 firm standalone reports | USA | OLS | Firm’s operating in litigation industries, firm’s early CSR reporting year, community, employee relations, environment, product disclosures |

| El Ghoul et al. (2011) | 1992–2007 | 12.915 firm-year observations | USA | Multivariable regression model, Blundel & Bond for endogeneity effects | Employee relations, environmental practices, product characteristics, diversity, community relations, human rights |

| Reverte (2012) | 2003–2008 | 114 firm-year observations | Spain | OLS | CSR quality disclosure information scores, sensitive industries |

| Xu et al. (2014) | 2009–2011 | 831 listed firms fragmented as 79.6% as state-owned enterprises and 20.3% as non-state-owned enterprises | China | OLS & 2SLS for endogeneity effects | Quality disclosures based on investors, employees, customers, suppliers, community, and environment scores |

| Dhaliwal et al. (2014) | 1995–2007 | 79,212 firm-year observations | 31 countries (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, India, Italy, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Philippines, Portugal, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, UK; USA) | OLS | Financial opacity and environmental, economic, social, and corporate governance disclosures in stakeholder-oriented countries |

| Feng et al. (2015) | 2002–2010 | 10,803 firm-year observations | 25 countries (United States, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Australia, China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, Taiwan) | Multivariable regression model | Environmental, social, corporate governance, and economic disclosures from Europe, US, and Asian firms |

| Harjoto et al. (2015) | 1993–2009 | 9259 firm-year observations | USA | Multivariable regression model and 2SLS model | Legal and normative CSR disclosures |

| Ng and Rezaee (2015) | 1990–2013 | 3000 firms | USA | OLS and 2SLS (lead–lag model for endogeneity) based on Ferreira and Laux (2007) sustainable business measures results and consisting of a lead–lag regression design. | Economic and economic dimension factors (growth, operation, research) and ESG performance |

| Kim et al. (2015) | 2007–2011 | 379 firm-year observations | South Korea | OLS and sensitivity analysis | Carbon intensity risk factor |

| Li and Foo (2015) | 2008–2012 | 1335 listed firms | China | Pooled cross-sectional time series regression model | Social responsibility quality disclosure from private and non-privately owned firms |

| Gupta (2015) | 2002–2012 | 23,301 firm-year observations | 43 countries (Australia, Belgium, Bermuda, Brazil, Canada, Cayman Islands, Chile, China, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kuwait, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, UK, USA) | OLS, Fama and McBeth two-step regression model, GMM by Arellano & Bover and Blundel & Bond for endogeneity | Environmental sustainability index (ESI) scores (emission reduction, product innovation, resource reduction) |

| Martínez-Ferrero and García-Sánchez (2017) | 2007–2014 | 8333 firm-year observations | 17 countries (Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, USA) | OLS and GMM based on Arellano & Bond | Assurance of sustainability reports by accounting & engineering firms. Pertaining audit firms, Big 4 is implemented when firms assured reports by accounting firms. |

| Suto and Takehara (2017) | 2007–2013 | 3556 firm-year observations | Japan | OLS and 2SLS for endogeneity effects lagging one-year CSP variable | Corporate social performance based on five criteria (employment, environmental, social contribution, institutional ownership, and internal governance) |

| Li et al. (2017) | 2009–2014 | 161 individual firms | China | OLS | Media reporting, carbon information disclosure, carbon information nonfinancial disclosure, carbon information financial disclosure |

| Eom and Nam (2017) | 2009–2013 | 86 companies | South Korea | OLS | Corporate value, socially responsible public trading in the KRX index, which represents a benchmark for CSR activities |

| Michaels and Gruning (2017) | 2013–2014 | 264 companies | Germany | Multivariate regression model | CSR scores based on artificial intelligence, CSR disclosure reports, sensitive industries |

| Weber (2018) | 2005–2013 | 260 individual firms | USA | OLS | Assurance of CSR report disclosed on a voluntarily basis based on GRI levels |

| Breuer et al. (2018) | 2002–2015 | 19,183 firm-year observations | 39 countries (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Philippines, Portugal, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, UK, USA) | Baseline regression model with fixed panel data variables | CSR engagement based on environmental, social, and investor protection disclosures |

Table 3.

Independent control variables based on the reviewed literature.

| Author(s) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richardson and Welker (2001) | Sharfman and Fernando (2008) | Dhaliwal et al. (2011) | El Ghoul et al. (2011) | Reverte (2012) | Xu et al. (2014) | Dhaliwal et al. (2014) | Feng et al. (2015) | Harjoto and Jo (2015) | Ng and Rezaee (2015) | Kim et al. (2015) | Li and Foo (2015) | Gupta (2015) | Martinez-Ferrero and Garcia-Sanchez (2017) | Suto and Takehara (2017) | Li et al. (2017) | Eom and Nam (2017) | Michaels and Gruning (2017) | Weber (2018) | Breuer et al. (2018) | El Ghoul et al. (2018) | Li and Liu (2018) | |

| Size—Market Capitalisation | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||

| Size—Total Assets | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Industry Variables | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Industry Dummy Variables | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

| Leverage | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Net Working Capital | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Return on Equity | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Return on Assets | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||

| R&D | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Advertising Intensity | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Earnings Variance | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sales Growth | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Business Segments | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Foreign Operations | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Foreign Operations Loss | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital Expenditure | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnover | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Growth in Sales | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating Income Growth Rate | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Accruals | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Profitability of Bankruptcy | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Bank Dependency | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Foreign Ownership | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Beta | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Analyst Following | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Analyst Dispersion | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

| Media Reporting | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sensitive Industries | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Analyst Following Social & Financial Disclosures | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| State Ownership | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Country of Origin | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Inflation Rates | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||

| IFRS | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Government Efficiency | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| GDP Growth | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Interest Rates | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Accountability | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Investor Protection | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of Stock Exchanges | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Yuan Risk Free Rates | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of Employees | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sales per Employee | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dividends Per Share | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

© 2020 Copyright by the authors. Licensed as an open access article using a CC BY 4.0 license.